Ofsted Chief Inspector Amanda Spielman launched the department’s proposals for its new education inspection framework last week. As well as broadening the inspection lens to look at overall curriculum and learning, rather than just maintaining a narrow focus on data and league tables, she also started a welcome debate about off-rolling. This is the process used by schools who seek to push out less able children, particularly as exam times approach.

The issue has grown in prominence over recent months, with both the Children’s Commissioner and the Association of Directors of Childrens Services (ADCS) raising concerns over the increase in exclusions. They are particularly worried by the number of children now being electively educated at home, as this group is effectively hidden from view.

However, whilst Ofsted have described their new framework as ‘covering all the way from birth through to adult learning’ it fails to address the question of responsibility for assessing quality and outcomes for the increasing numbers of children who are home-educated.

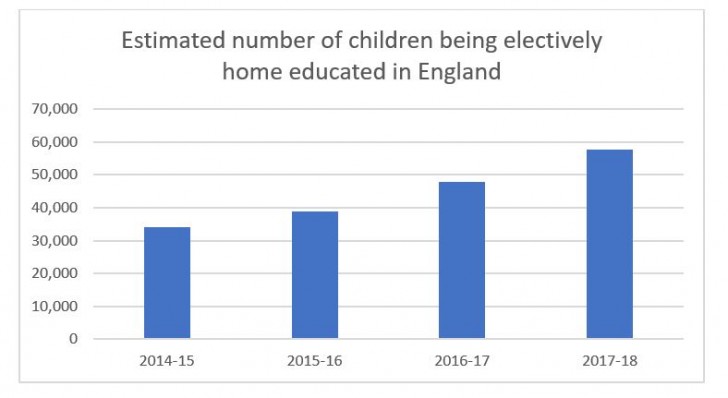

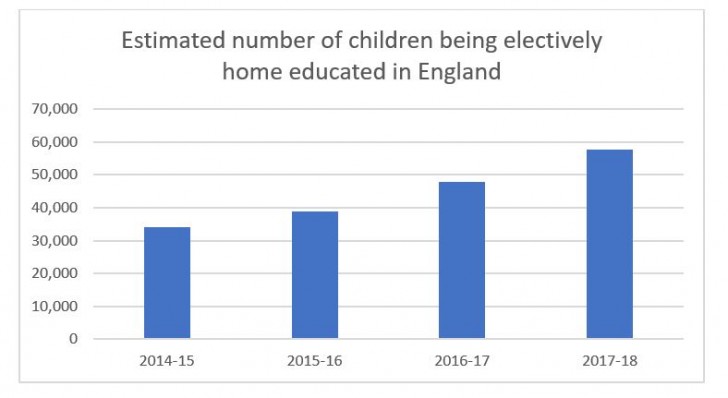

According to an investigation by the BBC, there were approximately 48,000 children being educated at home in 2016/17 – an increase of 40% since 2014. A survey completed by ADCS in November 2018 estimated that current numbers are now closer to 60,000.

However, the truth of the matter is we simply don’t know the exact number – as there is no national register on the number of children educated at home in England. This lack of data has long been recognised. Indeed, as far back as 2007, a research report by York Consulting on the prevalence of Home Education in England found that ‘there are no reliable data on the number of children educated at home. Available statistics are inconsistent and there is no officially recognised source’. But nothing has been done about it.

Ofsted has itself published data which demonstrated that in 2016, 19,000 schoolchildren who would have been expected to progress from Year 10 to Year 11 did not do so. Whilst approximately half of this cohort were subsequently found or turned up at a different school, the other half did not – effectively disappearing from the education sector and the protections it offers. That’s nearly 10,000 children dropping off the radar at a critical point in their education journey.

We also know that:

So how is the education, opportunity and aspiration of these children being assessed – in other words, who is ‘valuing’ the lives of these children?

Whilst a register of these children would be beneficial to at least understand the scale of the group and how it is evolving, this in itself will not tackle the issues behind it or ensure that home schooling is of sufficient quality. Local authorities do not have the power or resource to sufficiently do either of those tasks, and the splintering of the education system has made the system more complex than ever before. It is true that local authorities can still influence the local education sector – but doing so requires the right people on the ground to analyse the data, forge relationships with local education establishments and make challenges where off rolling is suspected. The scaling back of education grants to local authorities and increase in academisation have made this role much harder, and there is now a scarcity of qualified advisors operating in this space as a result.

So why can’t Ofsted assess home schooling?

Given that Ofsted quite rightly sees itself as having such a key role for ensuring the quality of education for the more than 8 million children in schools and other institutional settings – as well as the expertise and evidence to assess what good looks like in these areas – why don’t they take the lead role in reviewing the effectiveness of education for those children who are educated at home? A local register and additional local resources to support local authorities in tracking and visiting these children would be a significant step forward. But there is also an opportunity to pilot a different approach, with Ofsted given responsibility for meeting, understanding and assessing the provision of this group of children.

If education settings were aware that Ofsted would be visiting samples of these children on an annual basis, they might think twice about the messages they give to parents – particularly if this evidence could then be used to challenge the issue of off-rolling in the school the child was previously attending. It would also give Ofsted an important glimpse into the lives and experiences of these children, providing rich knowledge and insight which would be enormously useful in their role as an inspectorate.

It is clear that there needs to be greater scrutiny over the practices of off-rolling and the new framework is an important step forward. But I can’t help thinking this is still an opportunity missed. Ofsted’s new education framework needs to be bold if our society is serious about valuing education for all.