Consolidating the future of the NHS

Consolidating the future of the NHS

The NHS England planning guidance was published at the end of March, and the key word in the document is…

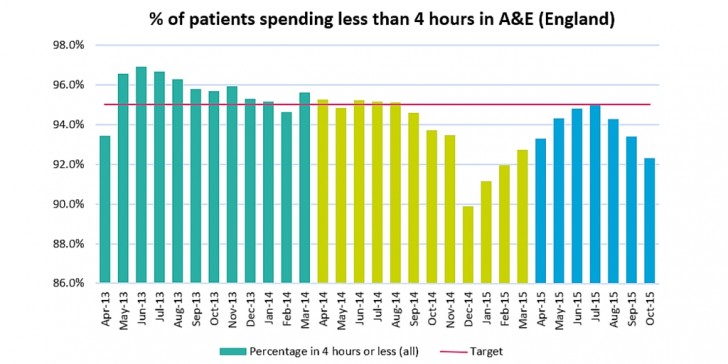

From the media perspective, the most commonly reported measure used to judge the NHS is that 95% of patients should spend no longer than 4 hours in A&E. The target has not been without its critics but it is a helpful proxy measure of whole system performance, and can be used as an early warning indicator for wider problems across the sector, which in turn emphasise the need for a shift to prevention. We need to start looking to better answers for long-term problems.

Over the last 14 months, performance against this target has been variable and at times poor. Waiting times reached their worst levels in a decade in the winter of 14/15, with 14 hospital trusts declaring major incidents. The target has only been met once over the last year.

The data for November and December 2015 is not yet available, but early indicators measured by the Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM) suggest that 88% of patients were seen within 4 hours in November, and 86% in December. This winter looks likely to be the worst yet.

The RCEM winter flow project has tracked acute bed capacity across 40 trusts. Between 2 Oct 15 (when the project began), there has been a 1.9% increase in acute bed capacity. Instances of delayed transfers of care have gradually reduced, from a peak of 2,500 in the second week of October, to under 2,250 instances in the first week of December. These improvements are not being reflected in a corresponding improvement in 4-hour standard performance. So, we can view A&E performance and activity as an indicator of system health – at least in part – and demand pressure is rising and at a time when the Better Care Fund is aiming to drive down admissions.

The provider sector in the NHS already has deficits north of £2 billion, so increasing capacity to cope with emergency admissions seems like the wrong place to look. If the solution isn’t in improving capacity, then it must lie in better managing demand:

What can be done? Early results from demand management programmes, made inside and outside of the NHS Vanguards, and internationally, is promising. Solutions range from whole system integration, to targeted prevention work for specific pathways.

The Nuka system of care in Alaska, established in the late 1990s, incorporates a patient centred home care model, with multidisciplinary teams providing integrated health and care services in primary care centres and the community. This has resulted in improved access to primary care services, a 36% reduction in hospital days and a 42% reduction in urgent and emergency care services.

St. George’s University hospital in South West London is trialling a GP triage system with Care UK and Wandsworth CCG. Triage nurses and a GP act as a ‘front door’, identifying patients whose treatment may be more suited to a primary care service. The team then book a same day appointment with the appropriate service. This has reduced the number of patients being seen by the trust, and reduced waiting times for those who are acutely sick. Satisfaction rates have improved (with 83% of patients rating the service as very good or excellent).

IMPOWER is working together with Bromley CCG and the London Borough of Bromley to develop an ‘Integrated Care Network’ model based on preventative and proactive care. Three ICN hubs will each serve a third of Bromley’s population and comprise a group of GP practices, who will work together with dedicated and specialised networked support. Each hub will have an increased focus on consistent and coordinated case management of those people identified as being most at risk to encourage self-management, help effective navigation through the Bromley health and care system, make an effective short term intervention and drive reduced demand pressures. Through this significant re-gearing of focus and incentives we believe once the new system is fully implemented this model can help Bromley improve health and care outcomes and deliver estimated savings of around £12 million per year.

The new emphasis form NHS England on building long-term financial sustainability means it is time to develop radical approaches which link to national and international best-practice to help reduce demand pressures. At IMPOWER we have developed a methodology called Bending the Curve to help organisations to drive up outcomes and drive out costs at scale.

Poor performance against 4-hour waiting targets are symptomatic of a health and care system that is creaking. As we begin 2016, the focus of the whole system needs to be on how to effectively and safely direct patients to the right providers of care, at the right time. Without this, the elusive 4-hour target is unlikely to be met for another 12 months.